One of the most important tasks of an archaeologist on an excavation is to keep a diary in which to record daily work and eventual discoveries, a diary that thus becomes the main source of facts and details of an archaeological exploration of any kind. Keeping an excavation diary is a sort of obligation towards both the past that unfolds before us and the present and future generations that expect us to take care and attention to preserve the discoveries. Even the archaeologists of the past have not shirked this obligation: there are some diaries of excavations from centuries ago that are extraordinary texts (such as, for example, the eighteenth-century diaries of the discoveries of the Vesuvian cities, which take us by the hand on a tour of wonders to places that are still mythical today), but all of them, even the lesser-known ones, maintain a charm that those objects that act as a bridge between us and the thinking of our ancestors know how to have.

One of the most interesting diaries for catacomb archaeology is the excavation diary of the Swiss Paul Styger, archaeologist and scholar of Christian antiquities in Rome, professor of archaeology and religious arts in Poland and one of the protagonists of the potpourri of nations that was the horizon of archaeological science in Rome in the early 20th century.

Due to a series of fortunate circumstances (in particular, his proximity to the German circles in the Vatican that a century ago were carrying out archaeological research and museographic experiments in the Eternal City), Styger found himself -between 1915 and 1917- directing the excavation of the church of San Sebastiano on the Via Appia in Rome. This is a very important site: an ancient church that later became a Baroque jewel, but set on an extensive cemetery area.

Styger’s excavation is particularly concerned with investigating the area directly underneath the nave and the Platonia, with the intention of also tracing the tomb where, according to a tradition invented in the Middle Ages, the bodies of Peter and Paul extracted from their original tombs in the basilicas of the same name would have been temporarily protected.

By Elzbieta Jastrzebowska

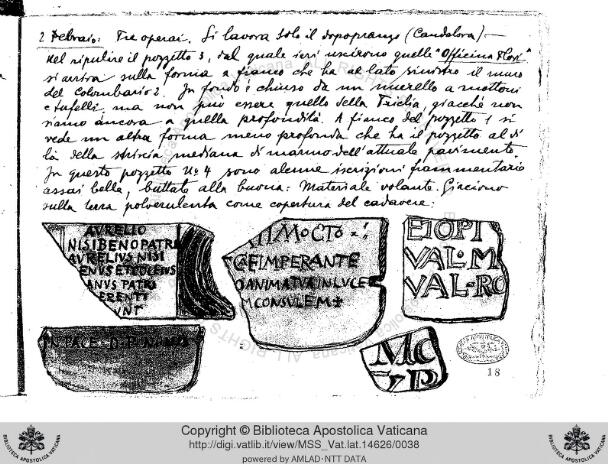

The diary is a little gem. It starts on 8 February 1915, ends on 27 February 1917 and is a mixture of text and pen illustrations, later coloured in watercolour. It is a true snapshot of what it must have been like to manage an excavation at the time, with constant inspection visits by the Ministry of Education and the Commission of Sacred Archaeology, fluctuating relationships with the workers, and more or less long interruptions for various reasons. The most beautiful feature are of course the drawings, not only of the individual objects found, but also of some of the structural situations found during the excavation.

The diary arrived in its current location in the Vatican Library after Styger’s death in 1939, by his own will, after having been missing for a while. This is confirmed by a letter pasted at the end of the manuscript, in which his sister refers to a certain Gerke who will help her find this diary and donate it to the library. At the end of this letter, an anonymous hand adds, in pen, that he received the diary on 31 May 1939 and adds: ‘And Gerke, if I am not mistaken, is the Nazi whom those of the Commission of Sacred Archaeology allowed to examine the excavations of the catacombs with all freedom, while they would have obstructed the Styger’. A small note full of implications, which relates to the strong relations between archaeological bodies and certain authoritarian political parties in the 1930s and 1940s, an issue that archaeological historiography has yet to come to terms with.

As an appendix to the diary, there are some typed sheets, with pencil-drawn illustrations, in which Styger lists pieces found in various catacombs during the 1920s, which were then lost, either because they were left on the site and treated carelessly, or because they were not handed over to the Vatican Museums. This list, too, is a singular evidence the practices of preserving artefacts: not a few objects were damaged by handlers who had ‘tried to tear them off’, or because they were left ‘without any precautions to save them’.