A general reconstruction of the history of catacombs rediscovery in central Mediterranean have to involve the catacombs of Siracusa, in Sicily.

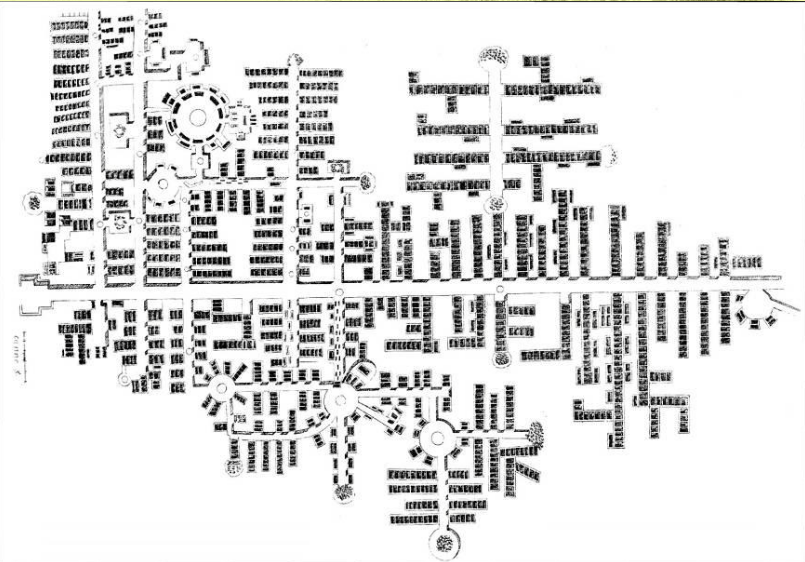

The most important underground Christian cemetery of the city is the catacomb of San Giovanni. It was built at the beginning of the 6th century and continued to be used throughout the 4th and 5th centuries, until the early decades of the 6th century. The cemetery is built using an ancient aqueduct and its ancient cisterns, acquiring its typical character of perpendicular galleries (with the central decumanus maximus and the various cardines that intersect it) with various rotundae, the cisterns that were later transformed into burial chambers. It also features a large number of arcosolia with multiple burials, important paintings, and a remarkable collection of epigraphs, mainly in Greek.

The catacomb and its surroundings were always known to the citizens. The first to describe it and record its layout was Vincenzo Mirabella (1613), but it then became a focal point for all European travelers visiting Sicily. Many of them described it and published drawings of the layout (including Jean Houel, Dominique Vivant Denon, and others). From the end of the 18th century, it was known and explored by the city’s leading scholars, such as Gaetani della Torre and Giuseppe Maria Capodieci. With the establishment of the city’s Archaeological Museum, its directors took charge of the excavations, starting with Francesco Saverio Cavallari (the discoverer of the Aldelfia sarcophagus in 1872) and then Paolo Orsi, who brought most of the underground structures to light.

The objects found in the catacombs are currently stored and exposed at the local National Museum of Archeology “Paolo Orsi”. It is one of the largest museums in Europe in terms of size and contains the results of research carried out in the Syracuse area from the end of the 18th century onwards, with finds ranging from prehistory to the Roman era.

In 1780, Bishop Alagona inaugurated the Seminary Museum, which became the Civic Museum of the Archbishopric in 1808. After the unification of Italy, it was transformed into the National Archaeological Museum of Syracuse and opened in 1886 in a historic building in Piazza Duomo. From 1895 to 1934, Paolo Orsi directed the museum, expanding its collection with excavation campaigns in the area. Luigi Bernabò Brea, superintendent since 1941, proposed after the war the purchase of the Landolina villa for the creation of a new museum in its vast garden. The design of the sections, which began in 1961, was carried out according to a scientific order by Bernabò Brea himself and Gino Vinicio Gentili, while the design of the building was entrusted to architect Franco Minissi. The architectural structure and educational apparatus made it a truly avant-garde museum, which was inaugurated in 1988. With its various floors and 9,000 m² of floor space, it remains one of the largest archaeological museums in Europe. Over the years, the museum has undergone modifications and expansions.

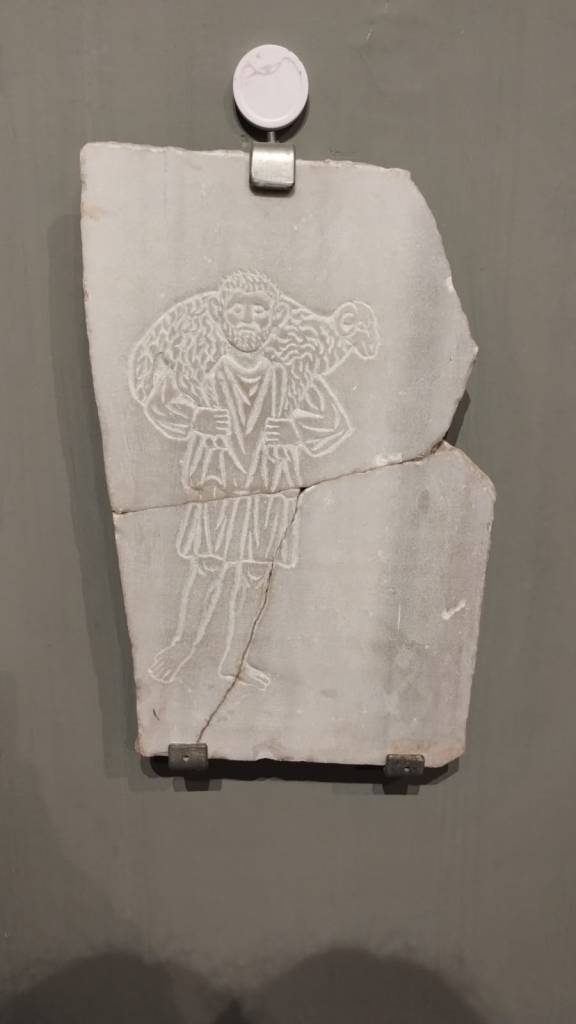

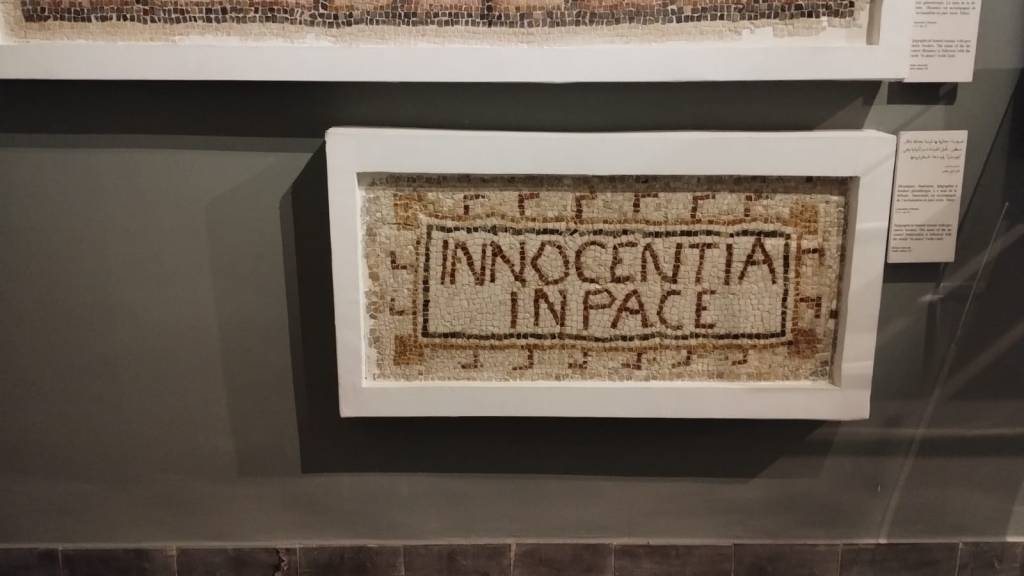

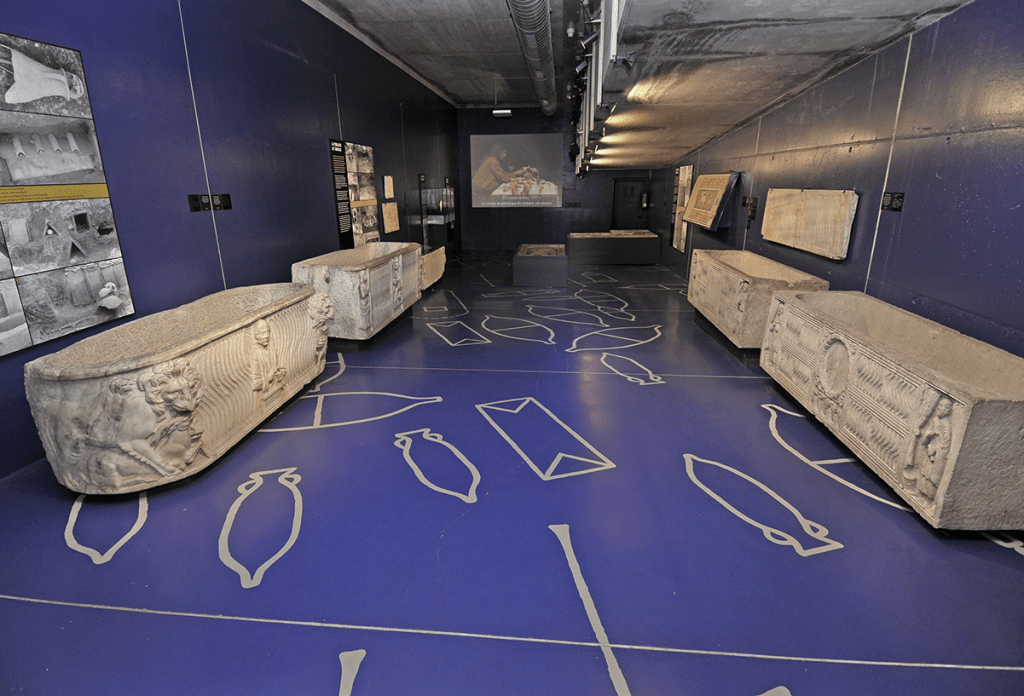

The entire F section on the first floor is dedicated to early Christian artifacts from the Syracuse area. It begins with an installation of the Adelfia rotunda from the catacombs of San Giovanni, with the sarcophagus of the same name at its center. The section mainly displays the most important Christian epigraphs of the sites and oil lamps found in the catacombs of San Giovanni, Vigna Cassia, Santa Lucia, and Cappuccini in Syracuse. The discovery of the Adelfia sarcophagus was undoubtedly one of the decisive moments in the creation of a museum in Syracuse.

The section has undergone two expansions: first in 2014 for the new display of the Adelfia Sarcophagus and other finds related to the catacombs of Syracuse, and now in 2022 for a renovation to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the sarcophagus.

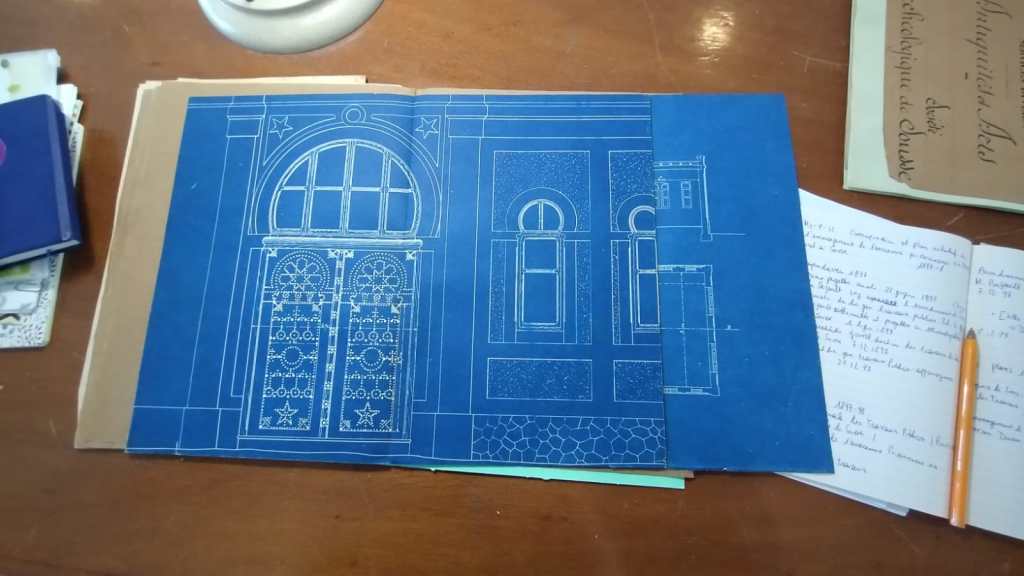

On the other hand, documents relating the catacombs throughout the centuries are stored at the Alagoniana Library and Diocesan Historical Archives of Siracusa. In the library there are abundant references and studies relating to the city’s numerous catacomb complexes, particularly in texts relating to the antiquities of Syracuse, written between the 18th and 19th centuries by various prelates of the city. These texts offer not only detailed textual descriptions of the sites and their state of preservation, but also a wealth of information on their use for scientific and religious purposes, as well as drawings of their layouts.

Of particular note among the manuscripts are:

Vestigij di Siracusa Antica Illustrata, C. Gaetani della Torre (1718–1805)

Raccolta d’iscrizioni antiche Siracusane, C. Gaetani della Torre (1718–1805)

Iscrizioni di Siracusa in numero 642, Giuseppe Maria Capodieci (1749-1828)

Gli antichi Monumenti di Siracusa in 54 volumi, Giuseppe Maria Capodieci (1749-1828).

Basic bibliography

Scandurra C., Un nuovo spazio espositivo sulle catacombe siracusane: il Settore F del Museo Archeologico “Paolo Orsi”, in M. Sgarlata, D. Tanasi (edd.), KOIMESIS. Recenti esplorazioni nelle catacombe siracusane e maltesi, Parnassos Press 2016, pp. 151-184.

M. Sgarlata, S. Giovanni a Siracusa, Città del Vaticano 2004.

M. Sgarlata, L’architettura del sotterraneo a Siracusa nelle memorie di eruditi e viaggiatori del Settecento, in Annali del barocco in Sicilia. Ediz. illustrata. Vol. 8: Siracusa antica e moderna. Il val di Noto nella cultura di viaggio, Roma, 2007, pp. 25-36.

M. Sgarlata, La raccolta epigrafica e l’epistolario archeologico di Cesare Gaetani conte della Torre, Palermo 1996.