Summary of the speech read at the XXXI Aiscom Colloquium

The mosaic heritage in catacombs is very limited and concerns ‘three species of mosaic works’: the floors, the slabs (marble or fictile) closing the tombs decorated with series of tesserae, and finally the wall mosaics decorating the arcosolii or the walls and vaults of the cubiculi. I will not refer to catacomb mosaics in general, but focus on a few cases and their collecting fate.

The history of mosaics in museums for the first centuries of the Modern Age has some shadows. For the 16th century, for example, we have little information on pieces of Roman floor mosaics in collections, but I would like to point out that in Chapter VI of Giorgio Vasari’s Vite, Del modo di fare i pavimenti di commesso, in the chapter on architecture (and not on painting…) he comments on the way Roman mosaics were executed ‘come se ne vede in Parione in Roma, in casa di messer Egidio e Fabio Sasso’. Moving on to the 17th century, in the collection of Cardinal Maximus, there was a ‘Stanza ultima de Musaici’, there was a special room adjoining the library, dedicated precisely to the mosaics in the collection. Even in the library itself, however, there were mosaics.

During the 17th century, coinciding with the extensive underground discoveries, the existence of mosaics in the catacombs was noted, and they too entered collections and the antiquities market.

Following a ‘translation of saints’ bones’ in 1656 the mosaic portraits of Flavio Giulio Giuliano and Simplicia Rustica were discovered in the cemetery of Ciriaca, detached between 1656 and 1677 from a tomb with their epigraph and acquired by the collection of Agostino Chigi. They were placed, as was the custom at the time, on the wall in the staircase leading to the Library, according to a design by Pietro da Cortona Chigi and in a pattern not unlike the one we have mentioned for the Massimo collection. An interesting contiguity, therefore, between mosaics and libraries. It was not until 1918 that the mosaics were detached and acquired by the Lateran Christian Museum, where they were again restored.

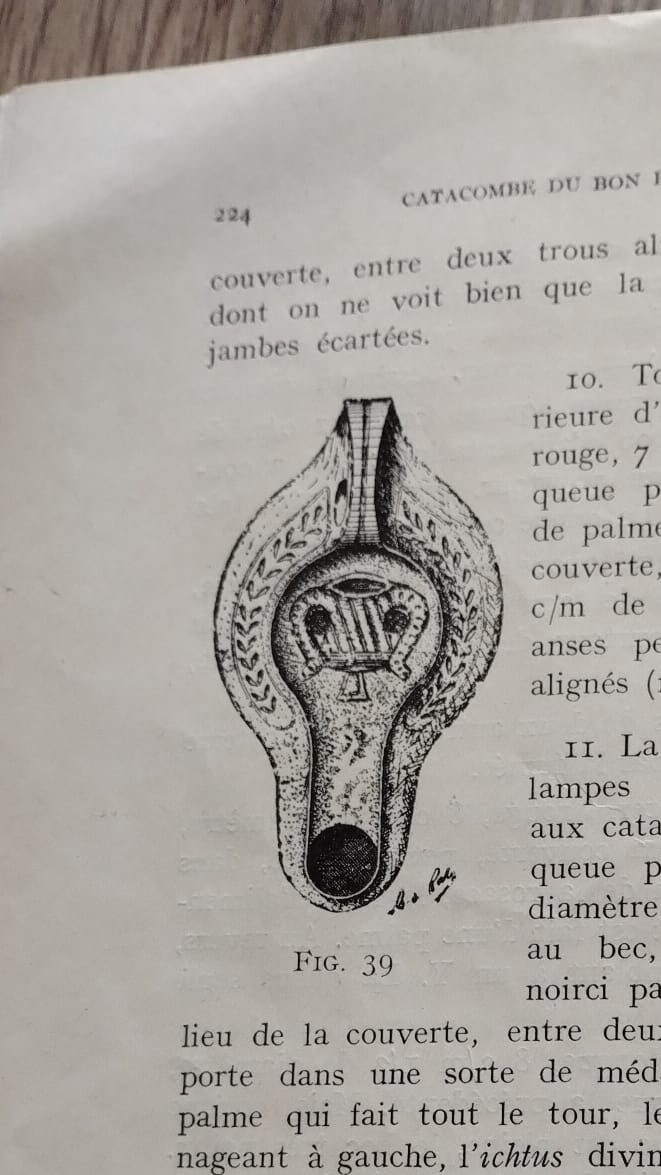

In the 18th century, the century in which mosaics made their entry into museums and collections, we find several testimonies of mosaics in the catacombs, without precise topographical references, by the Custodian of the Cemeteries Marc’Antonio Boldetti in 1720. He testifies of mosaic decorations on lithic or fictile supports, and is the main source on the topic for that century.

A couple of examples: Boldetti describes a brickwork from the cemetery of Ciriaca, on which there was a monogram between alpha and omega in mosaic tesserae. It is now lost, but at the time it ended in Gaetano Marini’s private collection. I do not think it is a coincidence that a mosaic artefact of this type, i.e. more epigraphic than artistic, aroused the interest of the leading epigrapher of the time, who was also the Vatican Librarian. Secondly, Boldetti draws a direct connection between some mosaics found in the catacombs and the Carpegna Museum: these are mainly ‘several birds and flowers formed on terracotta boards with non-ordinary artifice, and of minute workmanship’, i.e. emblemata, found between the Appia and Ardeatina roads, in particular at Callisto, used as closures for burial niches. All these pieces were later transported to the then Carpegna Museum in the Rione Sant’Eustachio in Rome, of which no further information is available afterwards.

In general, mosaics in collections in the 18th century had to be tear out and cut up to make more artefacts, for immediate placement in an antiquarian market. The 19th century in Rome marked the beginning of massive systematic excavations in the catacombs, the founding of the first institution for the protection of these monuments and above all the opening of a large museum dedicated to them in 1854 at the Lateran Palace, where the discovered mosaics were directly brought. In the Lateran Museum, they are displayed into the wall, following a practice that has been going on for centuries, inaugurated in papal museums by the display of the Dove emblema of Villa Adriana. Indeed, in the Lateran Palace hosted the important museum experiment of displaying the mosaic of the athletes of the Baths of Caracalla, discovered in 1824 and then placed in the museum in 1836, first in an imaginative reconstruction of the floor and then set into the wall, had been developed.

For our theme, an emblematic case is the brick with the mosaic image of a cock, a pavement emblem probably reused to close a niche. It was discovered in 1837 during the works of Virginio Vespignani in the cemetery of Verano, as stated in the sixth volume of Louis Perret’s disputed Catacombes of 1852, which places the mosaic to cover an unspecified martyr’s grave. Upon its discovery, it was sent straight into the Lateran Museum, where it was slightly restored and placed on the wall, in the large gallery of sarcophagi, along with all the other ‘sculptural works’, as noted in the catalogues of the time.

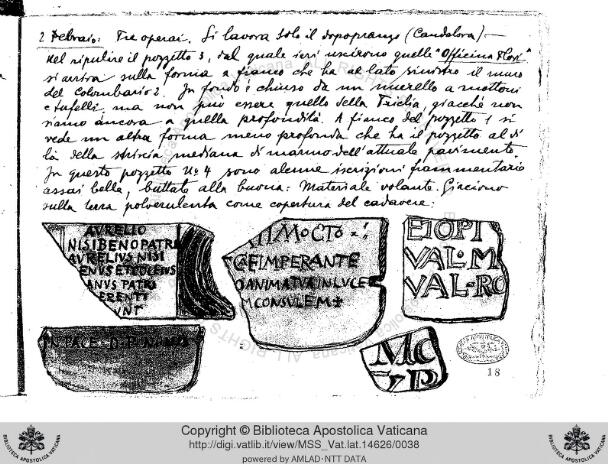

During the 20th century, the museum housed both mosaics previously housed in private collections (as the one in the Chigi Library which passed to the Laternanense Museum and then to the Pio Cristiano in the Vatican) and new discoveries, such as the two fictile slabs decorated with polychrome glass mosaic tiles from the Aproniano catacomb depicting three episodes from the biblical story of Jonah. They were discovered on 1 February 1938, the Pontifical Commission of Sacred Archaeology donated them to the Holy See and they immediately entered the Vatican collections, also becoming part, in 1963, of the new Pius Christian Museum opened in the Vatican after the closure of the Lateran Museum. Perhaps the most linear path in our little story.