[This is part of the text read during a public lecture at the Royal Netherlands Institute of Rome on 30 April 2025]

From the mid-sixteenth century, the discovery of many Christian catacombs in Rome spread knowledge about early Christian art throughout Europe, and made catacombs a popular subject. This process took place through promotion of academic studies, vast numbers of copies, and museum displays, all supporting the progress of archaeological discoveries. This phenomenon from the sixteenth through the twentieth centuries is obviously connected to political key events occurring in the Papal States.

One can say that the history of Christian archaeology cannot be divorced from the political and confessional use of the the catacombs. This use constantly characterised the work of many researchers and scholars, in periods when Christian archaeology was perceived as an official, national, catholic and papal discipline. They mostly fostered this relation between catacomb archaeology and politics through their scholarly publications and the production of copies of catacomb paintings. What is certainly evident is the key role of the papacy, which from time to time finds a political and cultural reason to reassert its authority through its most ancient past and claiming authority and exclusive control on it over the centuries, and playing a pivotal role in the process of dissemination of Christian art.

Catacombs for the Counter-Reformation agenda

Knowledge of the catacombs and the artistic treasures they contained was never totally ignored or forgotten contrary to long-standing assertions made by questionable but influential twentieth-century historiography. Records of pilgrims visiting the catacombs as part of the Christian-Rome cult circuit are numerous from the Middle Ages to the early modern age. Renaissance humanist scholars were the first to analyse the art of catacombs, often based on first-hand knowledge acquired during visits to the sites themselves. The scholarly impact of the construction of New St. Peter’s throughout the whole sixteenth century, an intervention that required extensive and lengthy excavations, was very important too: on that occasion, a significant number of sarcophagi, epigraphs and artefacts came to light, representing the first major contact for the modern world of Rome with early Christian art.

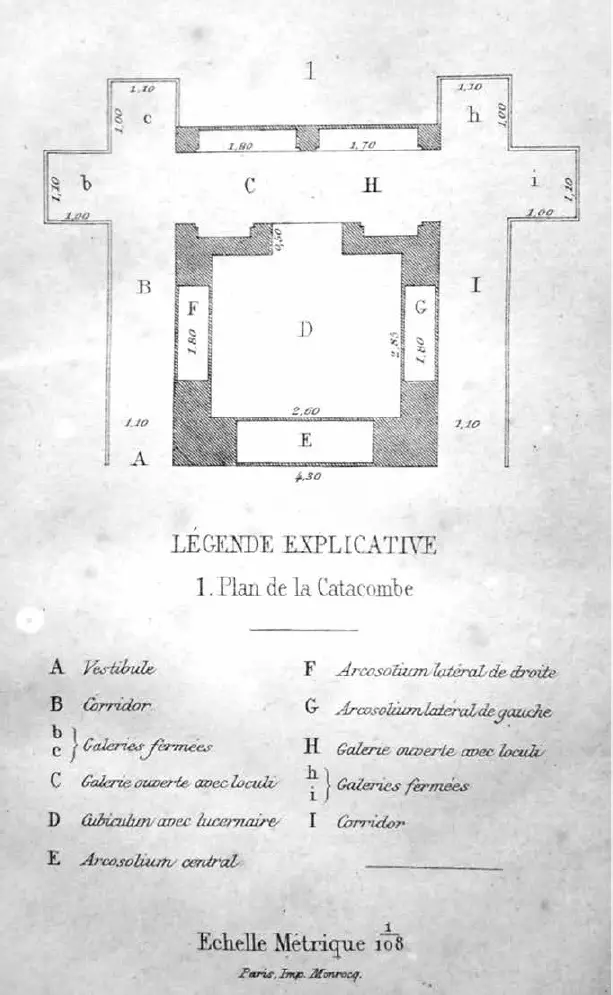

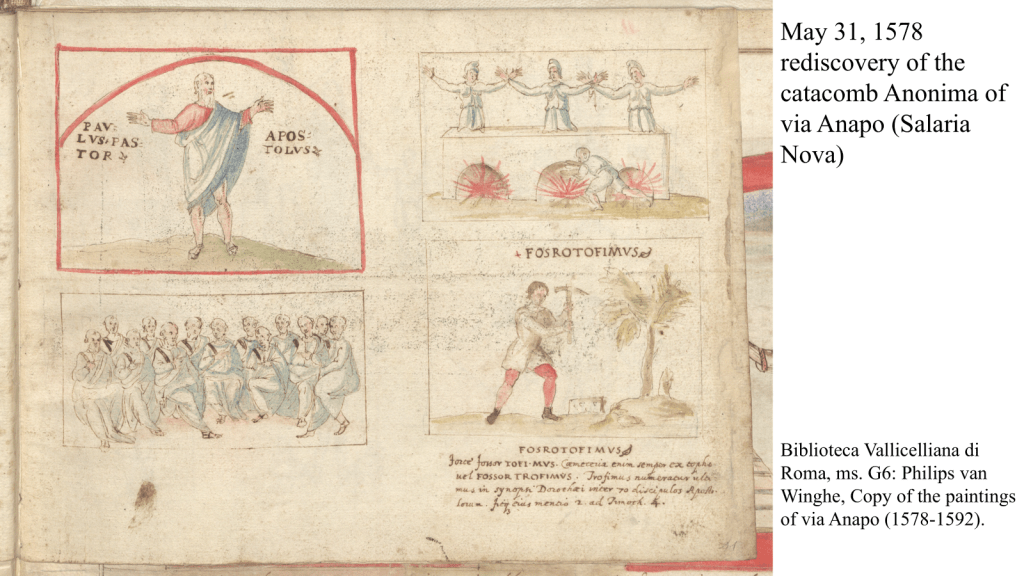

A crucial event happed on 31 May, 1578, during the pontificate of Gregory XIII: the accidental discovery of a Christian catacomb within the Sanchez vineyard on the Via Salaria Nova (at that time identified as the catacomb of Priscilla, but later in the late twentieth century as the Anonymous Catacomb of Via Anapo), with its impressive set of wall paintings. This is considered to be the moment when Christian archaeology began. However questionable that narrative is, this discovery nonetheless represented a real novelty involving sections of Roman population of the countryside, hitherto excluded from the rediscovery of and appreciation for Christian antiquities. These underground tunnels, marvellously decorated with paintings, totally unknown and extraordinary, attracted an incredible number of people, so much so that Gregory XIII decided to fence off the area (and then that the fence was torn down by eager groups of visitors), including not only clerics, scholars, and antiquarians, but also, and perhaps above all, ordinary people. This novel attention to of ancient Christian art is extremely interesting for the political and confessional use of catacomb art, because it appeared to have a great appeal for common people everywhere and could be used to convey Catholic messages in Italy and beyond. The first discovery of a catacomb also stimulated the search for more underground cemeteries throughout the Roman countryside, archaeological forays led by scholars, ordinary citizens, and different religious groups.

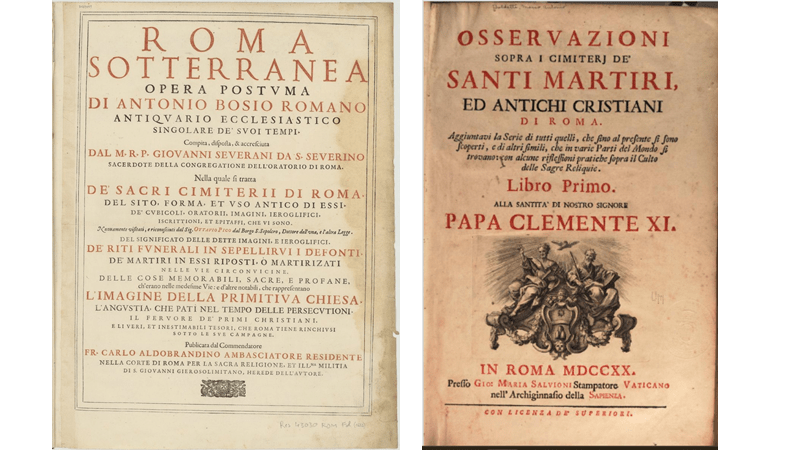

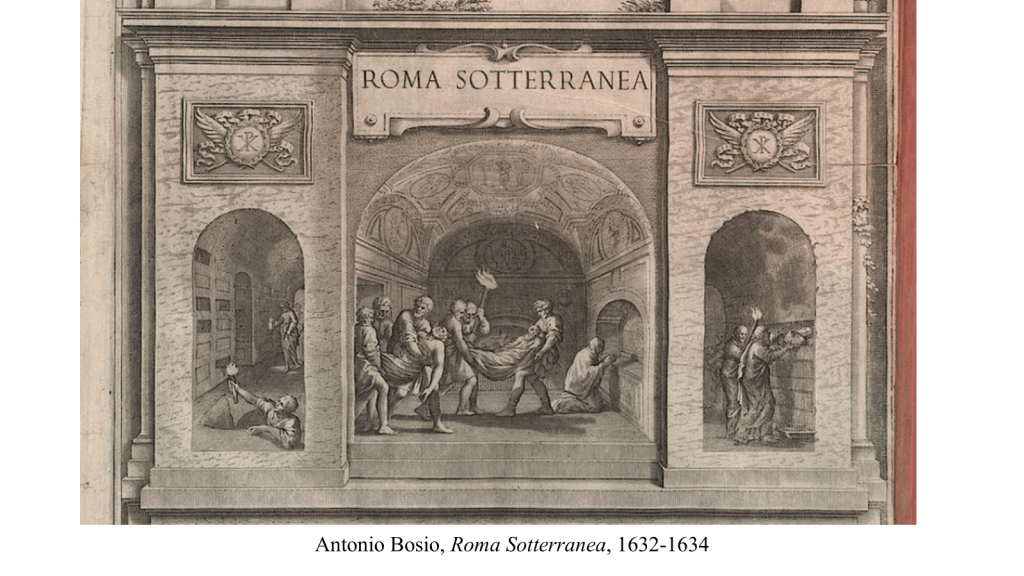

That feverish research culminated in 1634 with the publication of the first monograph on the Roman catacombs, Antonio Bosio’s Roma Sotterranea. This work and the explorations of catacombs led by Bosio increased indeed the international interest in the catacombs. While Christian cemeteries had already attracted the attention of scholars during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, after 1578, scholars or artists from all over Europe and Italy flocked to Rome with the intention of drawing and describing the paintings found in the catacomb galleries.

In a cultural context generally dominated by the new Tridentine needs in developing a new, unique artistic discourse controlled and directed by the Catholic Church, we must recall clear links between a genuine interest in Christian antiquities and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, with sacred antiquaria and apologetics in support of Catholic historiography. In fact, Roman and other European Catholic scholars of the second half of the sixteenth century were very keen to render service to the Catholic Church. Certainly, the findings, and in particular the paintings of the catacombs, could corroborate knowledge derived from literary and historical sources, and both could be used to legitimize a Catholic position against Protestant divisions. The most immediate interest was to record the paintings that were being gradually discovered during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in various Roman cemeteries. This was due to the intrinsic wonder aroused by the sight of such unknown, mysterious and yet so well-preserved Christian paintings, and to their clear link to scriptural episodes narrated in the early times of the new religion, but well known to contemporary Catholics and Protestants. These ancient paintings conveyed familiar religious stories and concepts, moreover in an easily understood visual language.

It was precisely the memory of a heroic era of the Church, of which the stories of saints and martyrs represented the main legacy, that produced a particular interest in the catacombs. In fact, a revival of early Christian themes and symbols, like palm as a sign of martyrdom, were used in all the arts to translate into images the Tridentine needs to create a set of iconographies to develop new resources for the faithful and new devotions to foster popular piety. This revival was translated into new styles, and tastes, as proven, for example, by the widespread diffusion of paintings with early Christian saints (Caecilia above all) in churches and private houses in the early seventeenth-century. Even the grandly Baroque architecture sought to make ancient Christianity present through the monumental recreation of early Christian liturgical spaces, which was one of the main aims of the great reconstructions of Roman churches financed by the various popes.

From a political point of view, the discovery, study, and recreation of early Christian art found in the catacombs therefore had a broad cultural role, expressed into two main directions. First, early Christian pictorial art was presented as incorrupt, pure, severe, and spiritual, thus the perfect vehicle for a process of artistic and figurative renewal of Catholicism that was to serve to counter Protestant criticism . Second, it is precisely the discovery of early Christian art and its clear message that served to convey and promote unbroken continuity of the Roman Church from apostolic times to the present. The catacomb images were very old; but in a certain sense, they were new too because they were reinterpreted as living images, models to be imitated, and a source of artistic inspiration.

Christian archaeology din late nineteenth century

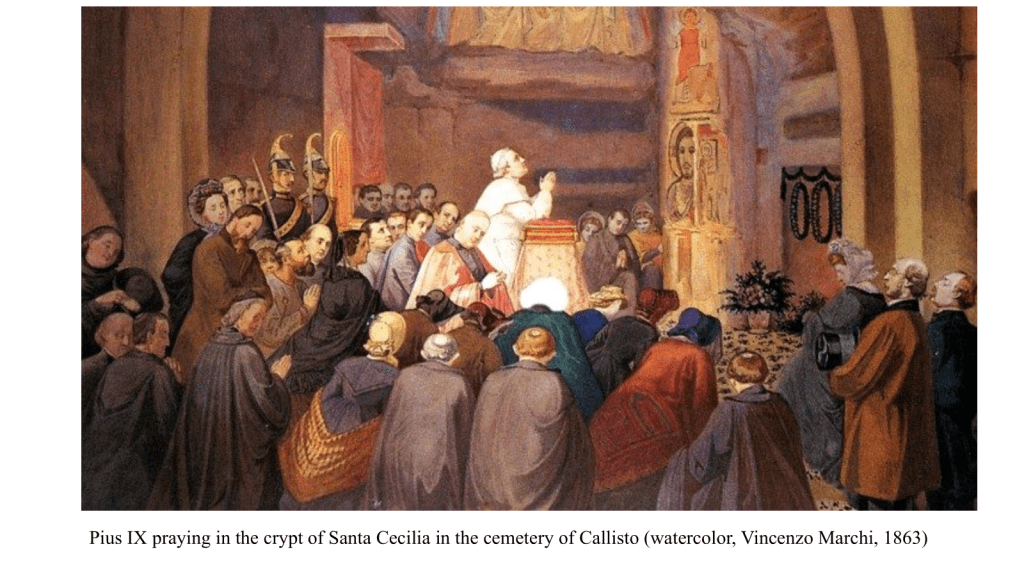

One has to wait until the 1850s for the next great change in the history of Christian archaeology to take place. Under the pontificate of Pius IX (1846-1878), in particular, the promotion of the excavation and study of Roman catacombs became extensive and more explicitly political. The Roman Republic (1849), the exile in Gaeta in the Bourbonic Kingdom and the return to Rome were the initial act of a pontificate characterised by perennial conflicts with the emerging kingdom of Italy that culminated in the end of the Papal States and thus of the popes’ political power in 1870. Given such political turmoil, unique in the history of the papacy, Pius IX was called upon to promote the papacy’s temporal power and Catholic Christianity with self-assertive policies at both the local and international level. Until the end of his pontificate, Pius IX insisted on the self-exaltation of Christian culture and the centrality of Rome in an international culture with ancient apostolic roots. Christian antiquity therefore assumed a key role in the cultural policy of Pius IX, who financed important initiatives for the development of the discipline of Christian archaeology. The Roman catacombs were proposed as a symbol of the times of persecution and thus a material embodiment of the martyrial narrative with which his pontificate was cloaked.

Events that supported this objective occurred in the first years of Pius IX’s pontificate. In 1860 Europe was in the midst of numerous social transformations, revolutionary uprisings and wars of independence due to nationalistic drives hostile to the great empires reformed after the Congress of Vienna. These upheavals resulted in the emergence of nation states, particularly in Italy, where the papacy lost its territory. In a slow political and cultural process culminating in the capture of Rome in 1871, Pope Pius IX (1846-1878) saw his temporal dominion reduced to the Vatican City. We were thus facing the most radical geopolitical change on the continent, in which the political as well as the cultural definition of nations played a very important role.

Under the cultural point of view, the pope made use of the work of the Jesuit Giuseppe Marchi (1795-1860), who is considered one of the founders of Christian archaeology as a scientific discipline, and Giovanni Battista de Rossi, who was then his young assistant. The two were put in charge of excavations in countless catacombs and were also entrusted with the dissemination their discoveries in textual and visual reports/accounts. They were also the protagonists of Pius IX’s major institutional foundations dedicated to Christian archaeology. The Commission of Sacred Archaeology (1852) oversaw the study and protection of the catacombs and other Christian monuments while the Lateran Christian Museum (1854) included a lapidary section to provide a proper place to display the many works of art found in the catacombs. It functioned, in effect, as an appendix to the visit to the catacombs, replete with didactic intents designed to advance the understanding Christian antiquities . Here, then, we are in front of a real state archaeology, scientifically conducted, but in the overt service of a political agenda. If that were not enough, there were large construction and restoration campaigns that became more customary as the situation became more complicated: think of the large investments for the restoration of the great early Christian basilicas such as S. Lorenzo fuori le Mura, Santa Maria in Trastevere, or even St Paul’s outside the walls after it was destroyed by a huge fire in 1823; as well as the celebration of the papal soldiers defeated in the battles against the Reign of Italy, who in the contemporary narrative rose to the rank of martyrs of the faith and received a monument in St John Lateran, the city’s cathedral.